Austin Rivers didn’t just take a shot at lazy draft discourse, he aimed at the incentive structure that keeps it alive.

“KD has gotten 100,000 guys drafted because people thought in their delusional minds they’re getting another KD,” Rivers said, arguing that front offices keep talking themselves into long, thin scorers as if the Kevin Durant blueprint is something you can simply photocopy. “He’s 1 of 1 type player. I’m tired of people see f*cking Thon Maker & they’re like ‘Kevin Durant!’ There’s only 1 KD.”

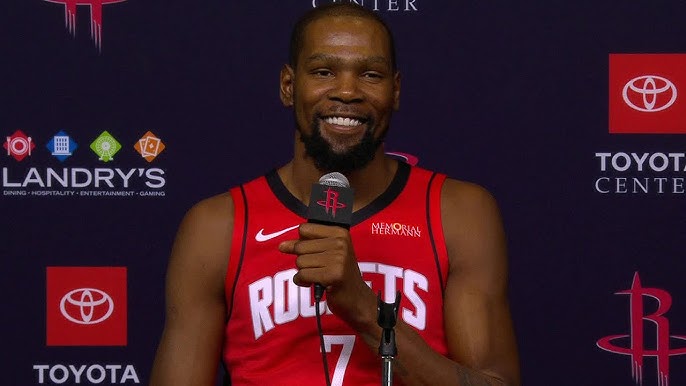

“Kevin Durant has gotten 100,000 players drafted because people thought in their delusional minds that they’re gonna get another Kevin Durant. There hasn’t been one since and there hasn’t been one before him. He’s a 1 of 1 type of player.”

—Austin Riverspic.twitter.com/Yf02BfPA9d

— ClutchPoints (@ClutchPoints) December 31, 2025

It’s a rant, sure, and “100,000” is obviously hyperbole, but the core point hits because it’s rooted in how the league drafts, talks, and dreams. Durant is one of the rarest player builds the sport has ever produced: a near-seven-footer who can score at every level, create off the dribble like a guard, and punish any coverage you choose. He was the No. 2 pick in 2007 and went on to win the 2014 MVP, multiple scoring titles, and championships, the kind of résumé that turns a single archetype into a decade-long obsession.

That obsession isn’t random. Modern roster-building is an arms race for tall wings who can shoot, handle, and defend multiple positions, the most expensive, scarce commodity in the league. If you can draft one, you save yourself from paying for one. If you can draft a super version, you change your franchise. And because Durant exists, teams keep convincing themselves the next one is out there.

Where Rivers’ argument gets sharp is in the way he links that chase to overreach: the leap from “intriguing physical tools” to “future Hall of Fame scorer,” powered by highlight reels, workouts, and a front office’s fear of missing the outlier.

Thon Maker is the kind of name Rivers uses because it instantly conjures that era of “unicorn” hunting, lengthy prospects being framed as perimeter-skilled bigs with limitless upside. Maker was drafted 10th in 2016 by Milwaukee, a 7-footer who arrived via the prep-school route and was marketed in part around unusual mobility for his size.

The problem isn’t that Maker was a bad bet in theory. It’s that Durant-level outcomes are so rare that using KD as the mental model skews expectations from the start, for executives, fans, and especially the player.

And that’s the real draft trap Rivers is calling out: when teams believe they’re drafting a type rather than a person. The league isn’t wrong to covet length, shooting, and ball skills. It’s wrong when the evaluation becomes cosplay, when a prospect’s frame becomes a shortcut to imagining a superstar instead of a prompt to ask tougher questions. Can he separate against NBA athletes? Can he make the second read? Can he score efficiently without being force-fed touches? Can he survive defensively when teams drag him into actions every trip? Most “KD comparisons” dissolve right there, because Durant wasn’t just tall and skilled, he was historically skilled, historically productive, and historically durable in the ways that matter for a heliocentric scorer.

Rivers’ frustration is also a critique of the language that surrounds the process. “Next KD” is a compliment that quietly becomes a demand. It inflates draft stock, then hardens into disappointment when the player turns out to be… a normal NBA player. And normal NBA players, especially tall ones with some touch, are valuable. They just aren’t Kevin Durant.

“There’s only 1 KD,” Rivers said.

That’s the line scouts and executives understand intellectually, but the market keeps testing emotionally. Because every draft is a lottery ticket, and Durant is the jackpot that convinces people the odds are better than they are.